by Suzanne Cadgène

MOTIVATION

Long days, long nights, high risk, largely unrecognized sacrifice, and the occasional bankruptcy. What madman makes this kind of career choice? Festival promoters, and there are hundreds of them. Some last for one or two seasons, a few last for years. We wondered how they got into the field, and how they survived and grew.

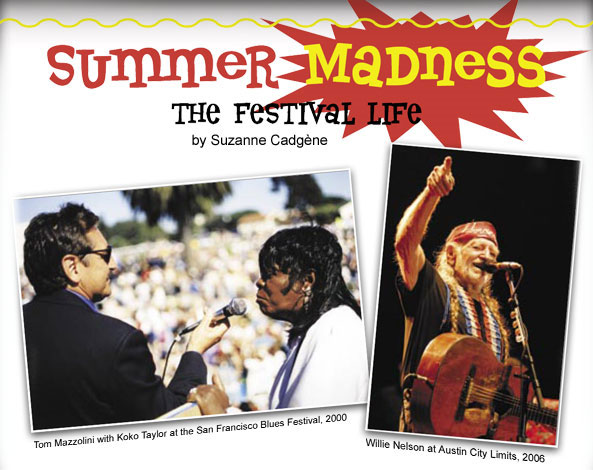

The original impetuses are varied. Michael Cloeren worked at a Poconos ski resort, and sought to make use of the facility in the off-season. Tom Mazzolini, working for the City of San Francisco, couldn’t find shows he wanted to see himself. Doc Watson wanted to honor the memory of his son. Whatever the circumstances, however, the underlying reason is really the love of the music, the desire to educate many people, and to present quality and diversity. It ain’t easy.

THE FIRST YEAR

That first step can be a lulu. Michael Lang, who had organized Miami Pop in 1968 and who today says “I’ve never been in the festival business,” made history with his second effort the following year, Woodstock. The first San Francisco Blues Festival, in 1973, aimed for the legal capacity of 600, but attracted some 2,000. Ted Boomer’s first festival created havoc, jamming Windsor, Ontario streets and the US Canadian tunnel, driving the police crazy. “It was great,” Boomer recalls. “We kept creating chaos, and because they wanted us off the street, they finally gave us the waterfront location we wanted.”

On the flip side, in Pinedale, Wyoming, a small festival turned into a debacle—complete with fistfights— when the original promoter failed to pay the bands, including Tab Benoit, who played even though he was stiffed. A blizzard hit the following year, and the festival opened to a crowd standing in icy rain and snow—in the third week in June.

Sometimes things work out as planned. Michael Cloeren ran a feasibility study in January of ’92, got approval in March, and the Pocono festival debuted that August 1 and 2 without a hitch, and has been profi table every year. Lori Dean talked to a landowner one Saturday in July, by Monday had insurance, dumpsters, porta potties, etc., and in early September produced 12 bands. When attendance doubled the next year, she moved to a campground, built a stage, and capped attendance at 1,000 for each of two festivals. The first year, Jerry Pillow borrowed a stage from a traveling preacher who came through Helena, Arkansas, and started the King Biscuit Blues Festival, now the Arkansas Blues & Heritage Fest.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

Most promoters put on a festival in their own community, designing the event around what works locally. A few promoters, like Charles Attal Presents, look for locations which will accommodate what they do best. Cities like San Francisco and Chicago have built-in audiences, while others, like Pinedale and Helena are The Big Event in a small community. Different strokes, but important distinctions. Successful promoters know their areas and their audiences, and what’s going to work there, not blindly emulate what works elsewhere.

The Pinedale Blues Festival takes place in the least populated part of the least populated state in the nation, in a town without a stoplight, so the key is finding headliners who will draw for hundreds of miles. The San Francisco Bay area, on the other hand, has lots of music venues and a million things for people to do.

Huston Powell, Charles Attal’s Talent Buyer, considers Austin’s Zilker and Chicago’s Grant Parks signature spaces, as important as the bands. His company looks all over North America for locations: the right site at the right time of year, where “you’re not right on top of one another.” Similarly, Lang books worldwide. He’s done a festival in France, is contemplating another event in Europe, and one in Bali at least two years out. His M.O. is to decide if everything is feasible, secure permits, and, ideally, take a year to organize it.

Festivals can have a huge economic impact, even in large metropolitan areas. You can’t find a motel room within a 25 or 30-mile radius of Rockland, Maine during the North Atlantic Blues Festival; when a family wasn’t coming back the next year, their motel held a lottery for the reservation. The festival actually closes off U.S. Route 1 on a July Saturday night, with bands on the highway. Director Paul Benjamin said “We definitely bring in millions to the local economy.”

In New Orleans, the city and the state depend heavily on Jazzfest and Mardi Gras revenues. Pocono Blues Fest, in August, is the biggest tourist weekend of the year in mountains which have been winter resorts for 60 years.

Be the first to comment!