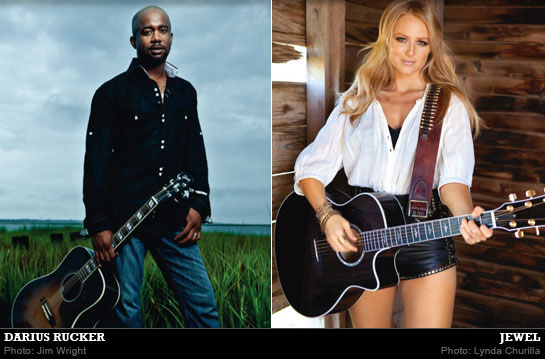

DARIUS RUCKER

DARIUS RUCKER WAS BORN May 13, 1966 in Charleston, SC. After a tough childhood with little money and less father, Rucker attended the University of South Carolina. When dorm-mate Mark Bryan heard Rucker singing in the shower, they formed a musical duo, then recruited Dean Felber and Jim Sonefeld to form Hootie and the Blowfish. A local reputation turned into a deal with Atlantic and their massively successful 1994 debut, Cracked Rear View, produced an avalanche of sales, hit singles and Grammys. The album has sold over 16 million copies, making it the 16th best-selling album in US history. While constantly touring, the band released the follow-up, Fairweather Johnson, in 1996. Understandably, its sales couldn’t match the debut’s, and Hootie and the Blowfish released three more successful albums, 2005’s Looking for Lucky being the most recent.

Hootie and the Blowfish is now on the back burner, though they play charity shows and some four concerts a year. Rucker’s prosperous solo career began with Back to Then in 2002, an R&B album whose sound was informed by Al Green, who Rucker covered on one song, and Jill Scott, with whom he collaborated on another. Rucker shifted to country for 2008’s Learn to Live, and again found great success. Lead single “Don’t Think I Don’t Think About It” hit Number One on the Billboard Country chart by October, and the next two singles followed suit. As the album passed gold and then platinum, Rucker racked up the Country Music Association’s New Artist award and made his debut on the Grand Ole Opry. We asked Rucker how he felt about being named “New Artist of the Year” 14 years after selling 16 million records. He smiled, saying, “I thought that was the country music industry’s way of acknowledging what I was doing, and saying that was cool.”

Switching gears yet remaining successful proved to be easier than Rucker expected. “I felt like I was starting over at square one. It was a surprise to find out how much Hootie and the Blowfish helped. But I heard Radney Foster’s Del Rio, TX 1959, in ’89, and ever since then I’ve been telling anybody that knows me, I’m going to do a country record someday.”

Currently, Rucker’s second country album, Charleston, SC 1966, released in October, is continuing his hot streak. “Come Back Song,” the album’s first single, marked his fourth Number One country hit. The album itself debuted at Number Two on the Billboard 200 and Number One on the country chart.

“This is a day job,” Rucker said. “I’ll probably be doing this until I die.”

JEWEL

BORN MAY 23, 1974 IN PAYSON, UT, JEWEL KILCHER’Searly life is defined by Alaska, where her family moved shortly after her birth. “We lived far from town. No running water, no heat—we had a coal stove and an outhouse and we mainly lived off of what we could kill or can. I loved it there.”

After her parents’ divorce, she stayed with her father, a working musician. With scholarships and donations from hometown supporters, she left for school in Michigan, at 16. Eventually landing in San Diego, local buzz from her performances resulted in a deal with Atlantic, and her smash 1995 debut, Pieces of You.

“My first record was considered a failure for the first year,” Jewel told us. In the middle of recording a second album, Bob Dylan asked her to go on the road, so she left the studio and went. “He really liked what I did at a time when nobody liked it. After his shows, he’d bring me down to his dressing room and go over my lyrics with me, give me books to read and music to listen to. He really mentored me.”

Jewel left Dylan and toured with Neil Young, another mentor. “I started getting some traction and ‘You Were Meant for Me’ just took off like a runaway train. I was selling 500,000 every week. Dylan asked me to open for him after that.” After Jewel’s set, while Dylan was getting ready to go on stage, he told her, “You sold a kajilion albums…In case you ever want to write with me” and gave her his number. She never called. “I always just figured he didn’t mean it.”

A slow and steady buildup of touring and hit singles eventually sent Pieces of You 12-times platinum, one of the best-selling debuts ever. Before releasing her sophomore album, Spirit, in 1998, she released a book of poetry, A Night Without Armor, one of her many extra-musical projects.

In the first of several stylistic shifts, she released This Way in 2001; its final single, “Serve the Ego,” a dance track, inspired her next album. The new sound didn’t last long, and 2006’s Goodbye Alice in Wonderland revisited the sound of her debut. Changing course again in 2008, Jewel released her country debut, Perfectly Clear, opening at Number One on the country chart. After an album of children’s songs, she released her second country album, Sweet and Wild, in 2010.

“I definitely love country, but that doesn’t mean that’s all I’ll do,” she said. “Dance singles are a lot of fun. It’s like coloring, saying are you just going to use yellow the rest of your life. I love yellow, I intend to use yellow, but I intend to explore the rainbow of colors.”

What are you listening to right now?

Darius Rucker: I listen to a lot of country radio driving around. Or I just put my iPod on random. My iPod’s all over the place. The other day I heard “Seven Chinese Brothers,” R.E.M.

Jewel: I’ve started listening to satellite radio. It’s fun to come across music, rediscovering stuff. Like the other night I was listening to Donovan’s “Cosmic Wheels,” and had forgotten all about that song.

What was the first record you ever bought?

What was the first record you ever bought?

DR: We had a lot of albums growing up, but the first two that were mine were two eight-tracks: Billy Joel’s 52nd Street and Barry White’s Greatest Hits. I would play them over and over. The next eight-track I got was the soundtrack from Convoy, the old Kris Kristofferson trucker movie.

J: Pink Floyd. I was six and I couldn’t read good and I thought it said “The Pink Panther.” It gave such a whole new spin. The entire time, I loved that record, I worshipped it. When I was older, at somebody’s house, the movie The Wall was playing and I was like, What the Hell? This isn’t the Pink Panther!

Where do you buy your music?

DR:There are a few mom and pop record stores in Charleston I like to go into, but I go to Wal-Mart or Target or on iTunes now. I’ve become an iTunes guy.

J: I love digital music. I’ve traveled since I was 18. Touring and schlepping around CDs was always such a pain that when we could start buying music on iTunes, I really loved it.

What was the first instrument you played?

DR: Drums. I got my first snare from my cousin and I played a lot in school. You know the guy from Loverboy? When he plays he makes really funny faces, and I made really funny faces, too. In middle school, I was jamming with a buddy and he laughed at my faces, and I stopped playing drums (Laughs). I figured if he’s going to laugh, it’s probably not what I should do.

J: Banjo. A girl in another family act in Anchorage, Alaska, where we were at the time, had a banjo and I loved it. My dad tried to get me lessons, but I was young and didn’t stick with it long.

What brought you to the instrument you now play?

DR:When I was 19, we started Hootie and the Blowfish and we realized we needed another guitar player early, so instead of getting another person, I just learned how to play the guitar. I didn’t have to play lead, so I just taught myself to play rhythm.

J:I wanted to hitchhike through Mexico when I was 16. My dad always played guitar in our act, so I thought I better learn a few chords. Three days before I hit the road, I learned A minor, C, D and G, in that order. I couldn’t go out of order because I didn’t know how. I couldn’t read music and I didn’t know tab, so I just started making songs up. It seemed a lot easier than learning other peoples’—it was really laziness that got me doing it. I’d get off the train and street sing and write about what I was seeing around me. I’d take the money I earned back to the ticket counter and see how far it would get me. It was a lot of fun when you’re 16 and too dumb to know better. I made it back to school and just kept adding verses to the song. I couldn’t change the chords for the chorus so I just changed the melody, and it ended up being “Who Will Save Your Soul,” my first song.

Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

DR:I’d kill to write with James Taylor. Or Elton John. I’d love to write a song with Michael Stipe. That part of it goes back to the days. In country music I’m fortunate to write with all the big guys in Nashville.

J: Bob Dylan offered, and I was always too scared to take him up on it. A lot of singer/songwriters don’t like to admit they co-write. I think it makes people better writers. I learned chord progressions and the way people put things together. I like writing all kinds of music too, so I enjoy writing with hardcore pop or R&B writers, but my favorite is probably Nashville—there are a lot of very talented writers there. Loretta Lynn had such a straightforward way, almost a colloquial approach, and I would have loved to write with her. I guess my number one favorite is John Prine. I love him. Every time I go to Nashville, I think I’ve got to call him and then I don’t.

What musician influenced you most?

DR:There are three. Al Green was huge with me growing up. When my mom couldn’t take the KISS records anymore, or when she couldn’t take me listening to those Beatles 45s for the 100th time, she’d take my record off and put on Al Green and say “Listen to this.” R.E.M., too. Huge, huge. And Radney Foster.

J: Probably my dad. I started singing in bars when I was about eight, so when there were bar fights I’d go hide in the bathroom until the cops arrived. Dad taught me a lot about performing and being professional and making sure you put your personal life behind you when you go on stage and do your job. He was really good at reading a crowd. I think those are skills; you have to be good at singing and songwriting to put your time in and your hours in, but being able to work a bar and a crowd that doesn’t want to listen to you is such an important skill for a young, up-and-coming person. I had so much experience by the time I was 18 that when grunge was huge and I was a folk singer with a guitar opening for the Ramones and Bauhaus, I was really able to capture the audiences’ attention because of what I’d learned from my dad. That gave me a big advantage. It would have caused a lot of other people to quit because it was just such hard going, such hard rooms to play. Each night has its own war. I was going to make that audience listen to me, and if I succeeded to some degree then I always felt proud. I enjoyed that. I liked the fight.

What was the song or event that made you realize you wanted to be in music?

DR: Since I was four years old, I would tell everybody I was going to be a singer. I’d sing Al Green songs to my mom or her friends using a little salt shaker like a microphone. It hit me when I heard “Hold My Hand” out of town for the fi rst time. Of course they played it in Columbia, big deal, we lived there. I went home to Charleston to visit my family and heard it on the radio and thought, Wow! This might actually happen.

J: I was raised doing it. It always was just a blue collar job to me. I never had stars in my eyes, never thought me in Homer, Alaska was destined for the big time. We made a living at it. It wasn’t like I moved to California to pursue a dream—I just had a sick relative there, and I helped take care of her. Circumstances just pushed me back into it. I got fi red from my job because I wouldn’t have sex with my boss, I got kicked out of where I was living because I couldn’t pay my rent and ended up living in my car. I kept getting fi red ’cause I kept getting sick. Then my car got stolen and I ended up homeless. The only thing I could think of was to get a gig like my dad, but I just didn’t know any cover songs because I just never learned guitar good enough to really figure out other peoples’ songs. The shows just built up and all of a sudden there were people lining out the door and I was doing two shows a night. Then a radio station put a bootleg on the air and all of a sudden record labels drove down. It was just very bizarre. Even when I got signed I remember thinking, There’s no way this is going to work, but maybe I could have a career like John Prine, like a good cult following.

Who would you like in your rock ‘n’ roll heaven band?

DR: On drums I’d put Stewart Copeland, and tell him at the beginning of the session, No we’re not going to play so much on every song. On bass, Dean Felber, the bassist for Hootie and the Blowfish. He’s my best friend. On guitar, Hendrix and Stevie Ray, for sure. Tower of Power on horns. I’d like Elton John on keyboard, not on chops so much, but on hang-out-ability, and he can sing backgrounds too. I’d be on vocals because I’m not cut out to do anything else (Laughs). A superband like the Traveling Wilburys, everybody sings. No harmonica, definitely not.

J: I’m not the most studied. I have a lot of friends that know musicians inside and out, but I don’t. I’ve been lucky to be able to play with many great musicians over the years. I think my favorite keyboard player is Spooner Oldham, who played on my first album. My first album’s band was kind of a dream band, the Stray Gators, Neil Young’s Harvest band. A guy named Ben Keith on steel, he recently just passed away, produced that album. Kenny Buttrey was a drummer. My bass player actually came up with the bass line for “Who Will Save Your Soul” and it sort of made that song.

What’s your desert island CD?

DR: Can I have a tie? It’d be a tie between Abbey Road, De l Rio, TX 1959 and Notorious B.I.G.’s first record. If I could have those three records, I could not listen to anything else for the rest of my life.

J: Definitely Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Songbook. ![]()

[…] the breakup of Hootie & The Blowfish, Darius Rucker has made a nice career for himself as a country singer. In recent years, he’s even found […]