By Mike Cobb

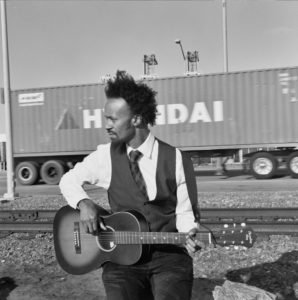

Mike Cobb talks to Xavier Dphrepaulezz, more commonly known by his musical moniker, Fantastic Negrito, about his amazing life journey, including running away from home at age 12 and surviving a near fatal car crash that left him in a coma for three weeks to an incredible rebirth, from winning NPR’s Tiny Desk Concert Contest in 2015, talking blues with Robert Plant and putting out The Last Days of Oakland, which just scored the multi-faceted “Black roots” performer his first Grammy nomination. For tour dates and more information on Dphrepaulezz, head to his website.

Elmore Magazine: You grew up in rural Massachusetts in a Muslim family, but when you moved to Oakland you shed that?

Fantastic Negrito: Yeah, I wasn’t cut out for organized religion. I knew that at a very young age. When I was twelve, I cut ties with the family, never saw my dad again.

EM: Wow. So how did that work?

FN: I just walked out the door and didn’t come back.

EM: No kidding?

FN: No kidding. I knew what I wanted at 12.

EM: Which was what?

FN: Freedom and insanity.

EM: And did they come your way, both of them?

FN: Oh yeah!

EM: So where did you go?

FN: I just hit the streets.

EM: I know Oakland has changed a lot, but it’s had the reputation in the past for being an edgy place.

EM: I know Oakland has changed a lot, but it’s had the reputation in the past for being an edgy place.

FN: I like edgy, and that’s why I left, because I prefer edgy. Because, out of edgy places and environments, that’s usually where great things happen. If you wanna get some you gotta pay! When we run away from edgy, as artists, things become boring, things become plain, and I’m not really that interested in that.

EM: So you would stay where you could?

FN: Yeah, you’d stay where you could; you know, at that age there were other kids that were kind of doing it, and you’d stay wherever you could, abandoned cars. If there was a nice, really nice square kids… I used to, you know, befriend them and make copies of the keys to their house, then you know the schedule, and then their parents leave and I’d go eat. You have to be crafty to survive at 12-years-old in the Bay Area. I don’t recommend any 12-years-old kids leave, but I just- I know my dad kinda prepared me in a very bizarre way. He was a very bizarre individual. He was born in 1905. He was from that old school, where kids probably did leave at twelve back then, you know?

EM: So you must have seen a lot out there on the streets of Oakland? What was it like at that time?

FN: It was edgy, it was exciting, it was dangerous, it was creative, it was irresponsible, violent, beautiful- all those things at the same time. Like, you know, the whole spectrum of life. But it was alive, I’ll give it that, and that’s what I really appreciated.

EM: I know it’s known for being the place where the Black Panthers were centered, but also the Hells Angels… so you had all that going on.

FN: It’s the birthplace of counterculture; the free speech movement took off there. Just the music that came out of there, the spectrum of the music, from E40 to Metallica to MC Hammer to Creedence Clearwater Revival; it’s just extremely diverse.

EM: I wonder why?

FN: Well in the Bay Area, I think we strive to be very original, and I don’t think we really worry about labels. We just worry about if it’s good and it’s original. It’s a pretty incredible tribe, the Bay Area.

EM: I haven’t been to Oakland in a long time, but from what I read, today it’s really changing, getting gentrified, and pushing a lot of the old out.

FN: That’s a lot of why I wrote The Last Days of Oakland, because it’s also the last days of Brooklyn, it’s last days of New Orleans. It’s just the acknowledgment and the peace of saying– You know what? If you keep looking for that thing that existed, you’re gonna be miserable. But if you just understand that everything changes, it keeps on changing all the time, I think it’s a much happier existence. And I like to be the bridge.

I’m from the old Oakland, but I’m an artist in the new Oakland. So, I know what that old Oakland was, and I know why you want to move there. It’s cool for a reason. People made it cool, and so it’s great to have this new energy come in; it’s amazing to see the city growing. It’s doing something different. But, don’t forget why it’s great, or it’ll cease to be that. You have to keep some of those broke ass artists around, because they’re gonna make it cool. And you have to make cities livable for people or they become these elitist enclaves. And we don’t need that in Oakland. We don’t have to open bars everywhere, and price everybody out, or it would be boring.

EM: Mm. Yeah, same thing happening here in Brooklyn.

FN: New Orleans, everywhere I go.

EM: Really– New Orleans? You’re feeling that?

FN: Oh yeah, everywhere man. But “the last days” just means “Hey, you know, it’s over! Something new’s beginning.” And it’s just very uplifting. I feel very optimistic, and I hope that people get that from the record. Some people are like, “It’s dark, it’s an angry record.” [laughs] I don’t feel like it is, and I can make an angry record, but that ain’t it. It’s just, as artists I think we have a responsibility. We need artists to filter all that and to be the voice of people and tell the truth, because I think we’ll be much healthier and happier that way.

EM: Talk to me about the interludes on the record. You’re getting a lot of messages across there, both through the songs and then, for example, on “What Would You Do?”

FN: I wanted to make that one because I want to contribute something. I’m part of this human family, part of this earth, and I think it’s really good to contribute. It’s new for me, because I used to be such a taker. I always call myself a recovering narcissist. Now I love to give something, and I wanted these kids to know, there’s tools when you’re stopped by the officers.

I’ve been stopped by the police all my life, but my father gave me tools. He would say, “Son, when the police stop you, you know this is what you gotta do. You gotta say “yes sir,” with no aggression.” When I was twelve on the streets, I had the tools to deal with these officers, and these officers who are committing these shootings are completely wrong. But at the same time, we have to know that this is what you’re gonna have to come up against, especially if you’re a young black or brown kid.

It’s the reality. The police stop me; they’re terrified. I see it. And I’m a weird dressing older brother now. [laughs] But there’s still this nervousness. I asked a police officer in Oakland, “Hey, so what do you think about these white cops that are shooting these black kids?” At first he was giving me the line, “We’re cops and black folks, we do kill each other.” But then he really started talking, and it came out. He’s like, “You know what it is?” He’s like, “They are not used to the actions and the attitudes of these brothers out here.” He’s like, “I know because I’m black; I grew up in these communities. So I know when somebody’s mouthing off or not complying all the way it’s just like looking at one of my cousins,” and I’m like, I agree– that these white officers are terrified. They think something’s gonna happen to them, and so they’re like “Fuck it!”

EM: Yeah, they equate simply being black with being ready to, uh… to I don’t know what!

FN: To get you! And since I was a kid, I’ve known this. I would look at cops and I’m like “Wow, they’re scared of me”– I could see it. But my dad was always there; before I ran away, he gave me these tools. So with these interludes, I really thought, why don’t I ask people on the streets, “What are you supposed to do when the cops stop you?” I’m not saying it’s fair; it’s not fair. I’m not saying that it’s right, it’s not right, but do you wanna keep your life? Do you want your mothers to keep burying these kids? And so my message is the same, that you have to learn that we’re up against the Gestapo here; you’re up against people who will kill you. Again, I’m not saying it’s fair. But we have a responsibility on the other side, and there’s always two sides. Whether you like it or not, there’s two sides, and I like having the conversation. I kinda like being the artist that’ll have the conversations that people don’t wanna have. If people wanna be in this relationship with America, all of us, we gotta start talking very real to each other. And that’s what I think the album is about, just talking real. Really looking for the solution, and looking for the roots of the problems and how we can deal with life.

EM: But it does seem so polarized these days, don’t you think? How do we cross that bridge? When you let the genie out of the bottle you can’t stuff it back in there.

FN: I think we gotta tell the truth, the truth helps, but it also hurts. And I just dropped my video of “In the Pines,” which pays homage and respect to women who bury their children. It happened in my family– my 14 year-old brother was a victim of guns. My 16 year-old cousin was. My friend growing up was, so that’s why. I always looked at the mothers, and I was like, oh god, what strength you carry raising these babies. You raise them, and then you bury them. And that’s a reality in our country, and we all gotta deal with it. If we don’t, what are we gonna do? We won’t grow as a country or as a society. So I’m not an activist. I’m not a political musician, none of that stuff. I just think about what’s going on. You talk about it if you’re an artist.

EM: But it’s pretty unusual to have that old Americana, whatever you want to call it– blues, bluegrass even, worked into this. It’s an interesting mix.

FN: Well, I like to call this music I play “black roots,” black American roots, and it really came from an experience. It came from, these people came over here, you know, and worked without getting paid, and something came out of that dark, edgy tragedy, like this music came out of it, and then this music spread out to everyone in the country. And it spread out to everyone in the world, and as you travel the world you can see the influence and results of this, what I call “black roots.”

When I was in England, Robert Plant came to my show, and so it was really interesting sitting in the East End, you know he’s watching me– it was a small pub. Then afterwards he calls me over and talk, and this is exactly what we talked about, you know, this. He was like, “You know I saw Skip James!” And I was just thinking like, Wow! This black American tradition is far reaching. They take it and then they do something incredible and they feed it back to us. And I go, “Wow! This is amazing!” Then I hear it, and “Here let me give it back to you!” And I think it’s just incredible! It was probably the best music conversation I’ve ever had.

It’s a far reaching hand, because it’s in everything. I hear it in E.D.M., disco, funk, electronics, in Metallica. It’s in everything! Those people that came produced something amazing. But they don’t have names. You don’t know who those people were. That’s why I call myself Fantastic Negrito, because it’s a tribute to them. The people that came over on ships; they had no name, and they really gave us all a gift. It’s exciting and inspiring and that’s why I did this project.

EM: I know you had a terrible accident, you were in a coma, and you’ve come out strong from that, from such a traumatic experience. You’ve obviously turned it around. From your point of view, what would you say you got out of that?

FN: I got everything out of it. It’s probably my third rebirth. And it’s probably the best thing that ever happened, because I could really see life for what it is. I could really appreciate every moment to this day, because I’ve been in that situation where you couldn’t even wipe your own ass or feed yourself– literally. And um… I’m grateful for everything. Whatever it is, I just take it and keep on moving, you know. I don’t know how to do anything else. I don’t know how to stop.

Everything that happens, it’s gratitude. Gratitude’s a good religion. You’re much happier and you’re much nicer to people ‘cause you’re just thankful. I’m breathing, this is incredible! I remember when my arms didn’t work, I couldn’t sit. The rehab for me was, you sit in a chair for three minutes. You know how many muscles it takes for us to sit? My God! So, it’s just such an awesome experience. I don’t wanna do it again. [laughs]

EM: Winning NPR’s Tiny Desk Concert Contest was a big breakthrough for you. I’ve seen it, and it was great.

FN: Thank you. Well, Bob Boilen, what a man, what a friend, what a genius, what a set of ears, you know? The Tiny Desk contest, when I heard about it I said, Eh, NPR, they’re not gonna be into what I’m doing. Even my lyrics. I’m clearly not politically correct all the time, and I’m offensive to some people. But I never would have imagined that they would put their neck out for me like that.

When I met Bob Boilen and really got to know him, I understood the marriage a little bit better, and it was something I didn’t wanna do. I’m in a collective, and I remember they had a vote, and then I had to do it, because that’s what a collective does– you vote. So it was like, one take, “I’m done! Goodnight!” I never thought of it again and then… To win, it was unbelievable. And I’m grateful.

EM: It was good for you.

FN: They’re amazing! I think they’ve given me a new lease on life as an artist, so to speak. Without them, it would have been a much harder hill to climb. Hi Bob Boilen!

EM: And the band is great too. Is that your regular working unit?

FN: No, I’m always changing it. Right now I have the guys that I took to Europe. I’m with them now. We really have gelled over there. You know, I move people around because I like to find people that don’t like what I’m playing. I don’t want “blues!” “I’m a blues guy, man!” I hate that. It’s boring. The guitarist I have is a Chilean, and he likes world– African music. But as I say, it’s one garden. You know it’s all from the same place. The bass player, he’s like into old school funk, and I’m like, Oh, that’s perfect! The organ player’s steeped in church! Perfect! They don’t even know who Skip James or any of these people are, so I say, perfect! So I like to keep an interesting band like that.

EM: They all bring something different, outside the box.

FN: It makes it edgy. They’re like, “Are you sure we don’t have a change here?” I’m like, No, there’s no change. Stay in E. I was like E man, I gotta stop writing in E.

EM: That’s interesting, because John Lee Hooker would usually stay in one chord, and the band would work around it. But he got so much mileage out of that, so much depth.

FN: Well, I think that it’s much more difficult to do a song with one chord. That’s difficult! And to have it be interesting. You could have a bunch of changes all you want– that’s easy. But I think that’s what really drew me into this old, black roots, Robert Johnson, Skip James, all these guys staying in one place, but so much feeling. I mean, just Robert Johnson alone changed the world. So, if it’s good enough for him, shit, it’s good enough for me. [Laughs] And you know we feel it. You know if I’m not feeling it, I know you ain’t feeling it.

EM: Yeah. Who else out there is doing stuff that you like?

FN: Um, obviously Chris Cornell; he’s amazing, especially touring in Europe with him. His Higher Truth album, I learned so much from Chris Cornell as a performer, as a guitar player, as a singer, as a human being, how to work a crowd. I remember when I heard Chris Cornell was looking for an opener I was like, forget that. He’d never be into what I’m doing. I was completely wrong. And when I got the call, I was a little terrified, like, What? You mean I have to stand up there with a guitar? That’s just crazy! I remember flying in from Austin, Texas to Oslo, Norway, and when I got there, there’s all these Norwegians sitting around and I was like, Holy shit, this is crazy! I remember I had a hat over my face the whole time playing; it was terrifying. But I watched Chris Cornell command an audience with his guitar, how he talked to them. It was a whole new skill set watching him.

I don’t like genres, I like artists. I love Kendrick Lamar. He’s inspiring. He’s doing things that are new and amazing energy, lyrics. Bold, man! He’s a guy that I dig, and I got to know a little bit about Sturgill Simpson, because I was gonna play with him, so I got to listen to his stuff and I’m really impressed. I think he’s trying different stuff. I like artists that are trying different stuff, like Kamasi Washington.

I’m not attracted to like the mundane, same old cliché stuff. I try to listen to everything; there’s a few songs on even pop radio I’m like, Oh, that’s pretty cool, but I don’t know who they are. [laughs]

EM: As you travel around the U.S. and Europe and the world, are there places you find that are more receptive than others? What kind of energies do you pick up?

FN: Every audience has a code, and it’s up to the performer to figure out what that code is. And that’s challenging and great, because when you accomplish it, it’s the greatest feeling in the world. Because you’ve made a connection. Music is the language of humanity. It transcends all barriers of language and culture, and I think people are receptive as far as you are willing to figure out that code. I played in Croatia and have had amazing concerts in Croatia! Then there’s been other places where I didn’t make the connection. But I look at it as it’s on me, not really on the audience. How did I relate to them? If they wanted to drink and talk, how do I play that music so you can drink and talk? And it’s fun!

Like Israel. They talk a lot, but you gotta figure that out. People get mad at me; people are always mad at me. “You said bitch, or nigga. Why did you say nigga?”

EM: You know I wanted to ask you about that; that’s a very charged word obviously.

FN: It is!

EM: And for different people they’ll react to it different ways. How do you feel about the power of language as a singer/songwriter?

FN: Well, I think that when you’re dealing with something that’s powerful and dangerous, you handle it very carefully. I don’t think it’s something you should just be frivolous about. You know you have a bomb; you don’t juggle it, kind of like nitroglycerin. When used, it’s for a purpose. Are you contributing something? Is it of value? Can people use it? And that’s why I wrote that song. “I dropped the E I added the A and I killed the R to heal my scars. Unless your people hung from trees and slaved ’til dawn don’t sing along.” It’s very simple.

I wanted to address that everything isn’t for everyone; that’s arrogance to think everything is for you. I know that everything’s not for me. It’s respect. Empathy is very good. If you’re contributing, be very careful, because you don’t want to create art to hurt people. You wanna inspire people, you want to keep it edgy, but it doesn’t mean to disrespect people or hurt people. I don’t wanna do that at all. That sucks. And there’s enough of that in the world. Politicians do that, you know, so why should artists? I think artists have a responsibility whether they want it or not, because we’re feeding people!

MC: So what’s next for you? What do you hope the future brings?

FN: Well, we’re gonna go up through the United States about twenty some odd dates. Then I have a tour where I’ll open for Temple of the Dog, and that’s gonna be big.

I have a new record I’d like to make. I left when I was twelve and I never spoke to my dad again, and I wanted to resolve that, and that’s a record I’d like to make. I think it’s the age old battle of the father and the son. “You hurt me, but you’re my hero! I’m a lot like you. Fuck you! I hate you, but I wanna be you! I mean, Why did you do this?’’ [Laughing] It’s fucked up.

EM: It’s the cycle.

FN: Yeah, but my father– I admire him so much. But man, what a tragic figure.

EM: How so?

FN: Well, he was born in 1905, if that doesn’t make you fucked up. [Laughs] He went through some stuff, man! And he was very intelligent, this guy. My father had a business here right in New York in the ’50s, and there was a lot of challenges, you know? You weren’t really treated like a person. In those days, black men born in 1905, I mean slavery was only, what, 27 years finished? He married my mom, she was 33 years younger than him, and he lost a lot of his kids. I wasn’t the only one who left and went into foster care. Maybe, like, five of us did. I’m a parent now, and I just couldn’t imagine losing my kid. I think that people will judge him for that. It’s very complicated, and he was complicated. I think he loved his kids, he was just broken. I’m figuring it out.

I’ve been writing, but The Last Days Of Oakland, it has legs. It just keeps on going. I’d like to shoot some more videos to “Scary Woman” to “The Nigga Song,” actually, do a video to the whole album. So, I want to just keep the conversation going and hopefully just keep contributing and playing shows. I love playing shows!

Be the first to comment!